Dr. Natalie Chen spent years digitizing fragile 19th-century photographs. Most of them blended—portraits, landscapes, and prim family poses. But one image stopped her in her tracks.

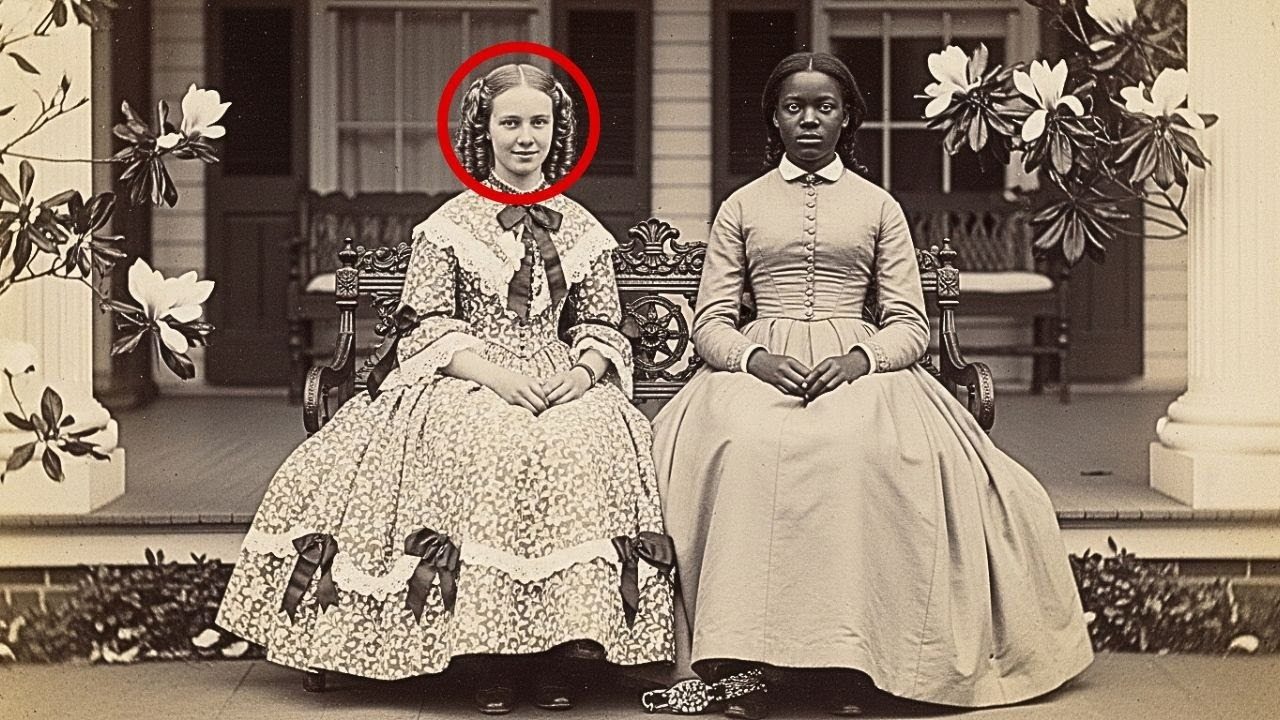

It depicted two teenage girls sitting side by side on a veranda in 1853. They leaned slightly toward each other, close enough to create the impression of friendship. Natalie was immediately struck by how deliberately “balanced” the composition seemed. For its time, the scene seemed almost too harmonious—carefully composed to appear normal.

But when she enlarged the scan, something near the hem of the black girl’s dress caught her eye. At first glance, it seemed decorative—some embellishment, perhaps a clasp. She increased the contrast, sharpening the details.

In that moment, the entire photograph changed. What looked like a tender scene of friendship turned out to be something far darker: control hidden behind sophistication, captivity disguised as grace.

In the archive, the original caption referred to the girl as “Harriet” and described her as a “companion.” The word did the heavy lifting—softening a harsh reality. When Natalie and her colleague, Dr. James Whitaker, read it, they both heard the same thing: someone had been trying to make this story more palatable for over a century.

Deep in the archives, they found a line in a purchase ledger that left no room for doubt: the young girl had been purchased as “the intended companion for Miss Caroline.”

A diary from the same family added something else. It mentioned “necessary precautions” and a “special arrangement” that would be “safe and appropriate.” The language was polite, even affectionate.

This wasn’t a concern. It was a sense of ownership. In the archives of the Federal Writers’ Project, Natalie later found an interview with an older woman whose story matched perfectly—same region, same time, same names. She spoke of a “gold chain” worn on the ankle, called a “special bracelet.” And she said something that stuck with Natalie:

“A chain is still a chain, no matter how beautifully you make it.”

Once the team figured out what to look for, they began to notice similar details in other photographs—small, easily overlooked signs of the same practice.

Natalie proposed the exhibition with a simple goal: to show how often history conceals cruelty behind beautiful images. Visitors would see more than just photographs—they would see old explanations alongside objective evidence. And they would understand how easily comforting lies can persist when no one looks closely enough.

Discuss

More news

Discuss

More news