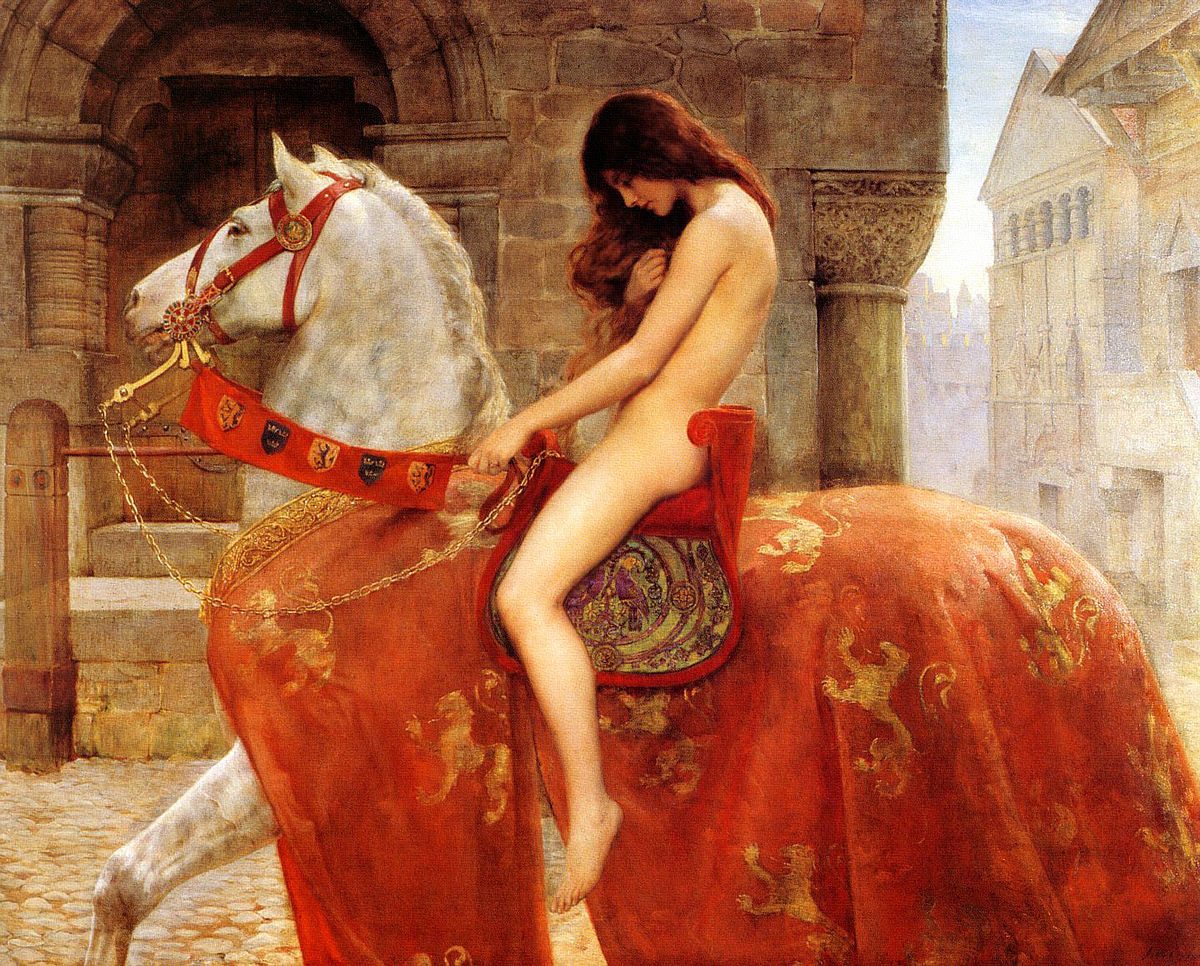

Lady Godiva was an English noblewoman who lived in the eleventh century AD. Although she belonged to the upper classes, the woman had a reputation for sympathizing with poorer people and was known as a person who loved charity. It was her concern for people experiencing poverty that gave rise to the most famous legend of Lady Godiva. It is because of this legend, in which the woman rode through town on horseback completely naked, that Lady Godiva lives on in our memories to this day.

Who was Lady Godiva?

As we know, “Godiva” is a Latinized form of the Old English name “Godgyfu” or “Godgifu,” which can be translated literally as “the gift of God.” Little is known of Lady Godiva’s early years.

The now-famous Lady Godiva is preserved in the records because of her husband, Leofric, Earl of Mercia. He was among the most influential English nobles in the eleventh century. When King Cnut of England died in 1035, Leofric supported Harold I. In 1051, Leofric avoided civil war because he resolved the conflict between King Edward the Confessor and the Earl of Godwin of Gloucester before the two sides met in confrontation.

Leofric is also remembered for being a benefactor of religious houses.

Among other good deeds in his life, he and his wife Godgiva, who was a great worshiper of God and loved the holy Virgin Mary, built a monastery entirely at their own expense, well endowed with ornaments to the extent that no other sanctuary in England could boast so much gold, silver, jewels and precious stones.

The first account of the famous story of Lady Godiva

However, the chronicler makes no mention of Lady Godiva’s famous trip. The earliest known version of this story is contained in the “Chronicle” by Roger of Wendover (a monk of St. Albans Abbey), which dates back to the 13th century. Under the year 1057 AD, the year of Leofric’s death, the chronicler writes that the Earl levied heavy taxes on the inhabitants of Coventry. Lady Godiva frequently urged her husband to stop taxing the citizens to make their lives easier, but all her efforts were to no avail.

Again and again, Leofric voiced his grievances to his wife, but Lady Godiva would not give up. Ultimately, her husband agreed to grant his wife Lady Godiva’s request on the condition that she is entirely unclothed through town on her horse. She agreed.

The woman stripped off her clothes, covered her entire body with her long hair, and got on her horse. Accompanied by two knights, Godiva rode through the city. After this, Leofric kept his promise, and the inhabitants of Coventry no longer had to pay taxes to the Earl.

As time passed, several different versions of this story emerged. The best known is Peeping Tom, which was added in the seventeenth century. In this version, Lady Godiva asked the residents of Coventry to stay home and not look at her as she rode through town naked so as not to embarrass her.

The residents complied with her request except for one man, Thomas, who couldn’t help himself and peeked at Lady Godiva. According to some versions, he went blind or died when looking out the window.

But was there a famous walk?

Some scholars argue that Lady Godiva’s ride was nothing but fiction. These scholars say that the trip in the nude should have made it into the chronicles of Lady Godiva’s time.

A medieval woman gave birth after her death.

Rare medieval skeletal remains excavated in Wales date back to the thirteenth century.

There is also debate about whether the reason for the supposed trip makes sense. Lady Godiva is believed to have had her power, wealth, and lands; some even say she should have handled land taxes, not her husband. When Lady Godiva was alive, she had the right to divorce her allegedly abusive husband and retain her inherited property and wealth.

Therefore, if she did take her walk naked, it was probably done as a religious penance rather than to try to remove taxes for the peasants. This charitable version of the story is more consistent with when it first appears in written sources (around the same time Robin Hood also appears).

Discuss

More news

Discuss

More news